In the 19th and 20th centuries, middle-class women in Toronto were largely confined to traditional roles as wives, mothers, and homemakers. It was only over time, influenced by societal shifts, that they began to work, pursue education, and fight for their rights. Their lives tell a story of a gradual transition from domestic labour to an active role in the city’s economic, educational, and social fabric. And it is thanks to them that Toronto transformed into the dynamic, inclusive city where women today pursue education, professional careers, and finally have their own voice. Read more on Torontonka.

Domestic Work and Housekeeping

Imagine Toronto at the end of the 19th century – a city where middle-class women had limited career options. Most were either homemakers or worked as domestic servants in other households. For many women in the city, domestic work became their primary source of income. They not only cared for their own homes and families but also performed various jobs that helped support their household budgets. This labour was so vital that it virtually sustained not only individual families but also the entire urban economy; without it, life in the city would have been impossible.

The daily routine of cleaning, laundry, and cooking was arduous, especially for those working for others. Women often lived far from their families, in rented rooms or shelters organized by churches and charitable organizations to help newly arrived immigrant women find work and avoid destitution. These “women’s hostels” became crucial support centres where women could find their first job, connect with others, and adapt to city life. Such jobs didn’t pay well and didn’t require specialized education, but it was thanks to these efforts that the homes of wealthier Torontonians shone with cleanliness, allowing those families to focus on their own work or businesses.

Even in such challenging times, these women found like-minded individuals and mutual support. They shared stories, helped each other, exchanged experiences, and even began to organize into small groups that later evolved into the first labour associations. This marked the beginning of a significant transformation.

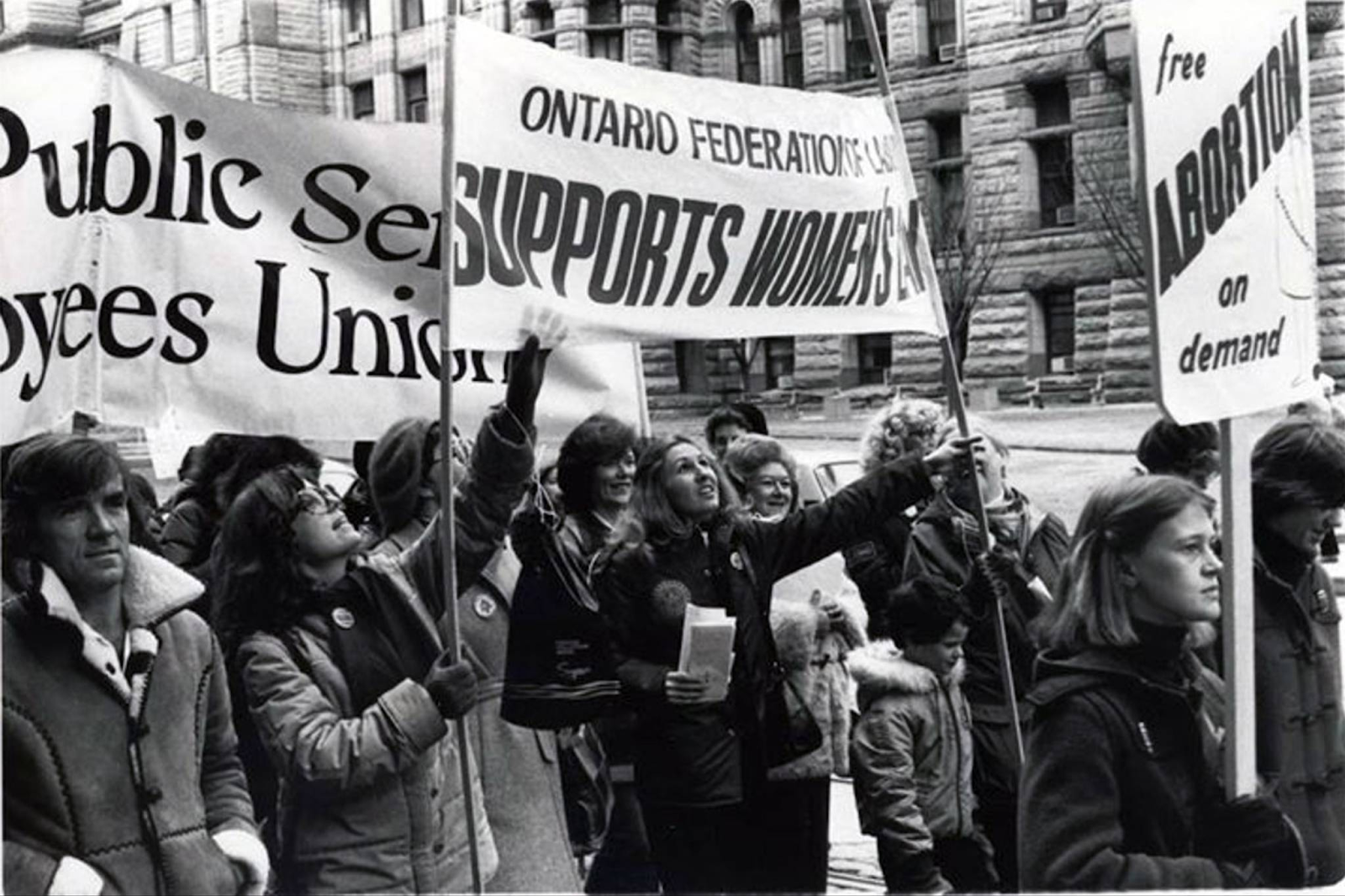

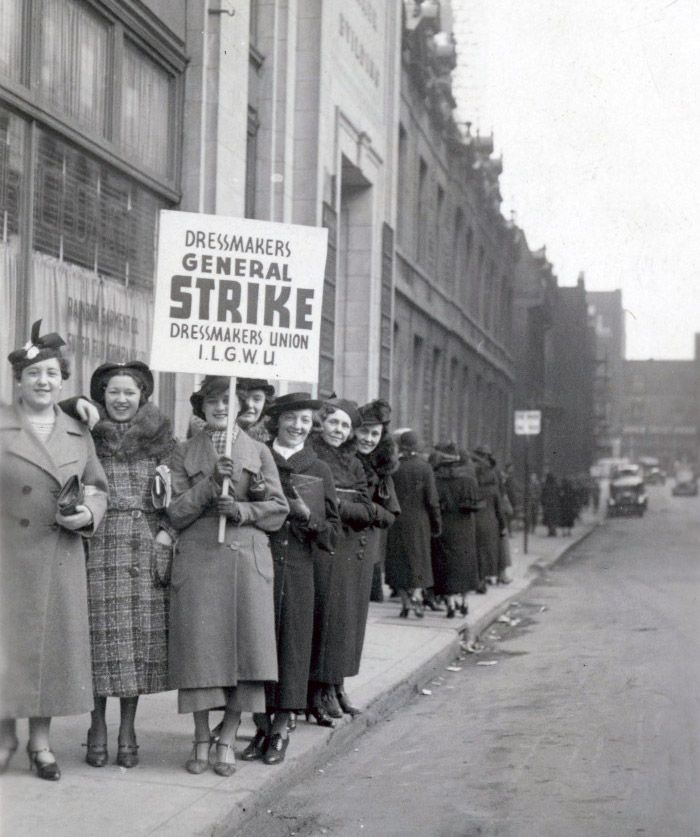

Textiles, Sewing, and the Rise of Women’s Unions

When we think about women’s work in Toronto at the turn of the 20th century, it’s impossible not to mention the textile and garment industries – one of the few sectors where women could not only earn money but also fight for their rights (at that time, most sewing workshops and factories were predominantly staffed by women).

This was grueling work. Long shifts, repetitive motions, low pay, and a lack of social benefits were the daily reality. They sewed dresses, suits, and sometimes even workwear for factory labourers, often in cramped and poorly ventilated spaces. Temperatures soared, and management demands were strict. Essentially, women worked like machines but were paid pennies.

It was precisely these conditions that spurred the need to organize. The first women’s unions in Toronto emerged in the early 20th century, as women began to collectively advocate for their rights. A notable strike movement occurred in 1902 at the Toronto Carpet Factory, where women demanded better pay and regulated working hours. This was their first step in the fight for decent working conditions. Later, telephone operators – another category of women often exploited – also broke their silence. In 1907, they went on strike, protesting against excessive workloads and low wages. This wasn’t just a desire to earn more; it was the first widespread realization of their own power and their right to respect.

New Professions: Doctors, Journalists, and Entrepreneurs

From the late 19th century onwards, women in Toronto began to break established stereotypes and forge paths into previously forbidden professions. While previously women’s choices were limited to domestic work or tailoring, now doctors, journalists, and entrepreneurs started appearing more frequently.

One of the pioneers in medicine was Dr. Emily Stowe, who in 1883 helped establish the Women’s Medical College in Toronto. She herself overcame numerous obstacles, from prejudice among male colleagues to the difficulties of studying abroad. But her perseverance opened doors for hundreds of women who dreamed of a career in medicine. In the same city worked Jennie Smillie Robertson – Canada’s first female surgeon, who proved that women in surgery were not an exception, but the future.

In journalism, Alice Freeman, a teacher who also wrote under the pseudonym Faith Fenton, covered issues of women’s rights, gender inequality, and social change. Her articles were often provocative, but by using a pseudonym, she managed to avoid censorship and the risk of dismissal. Equally renowned was Kit Coleman, who became the first female war correspondent, reporting for both the Toronto Daily Mail and other publications. Her work proved that women could be just as professional and courageous as men.

Women’s entrepreneurial activity in Toronto also grew gradually. Often, it was widows who inherited family businesses who became managers of shops, hotels, or even factories. They learned to handle accounting, hire employees, negotiate contracts, and repeatedly proved that a successful business does not depend on the gender of its owner.