During the colonial era, Christian missionaries often questioned the role of Indigenous women, though their connections with European fur traders facilitated interactions between their communities and the outside world. Throughout the colonial period, European women were encouraged to migrate to Canadian colonies, expanding the white population on the land. After the Confederation Act of 1867, their lives were shaped by federal laws and provincial legislation. Over time, women became integral to Canada’s labour landscape, weaving their contributions into the fabric of social movements and cultural change. However, the journey was fraught with discrimination. In 1918, a breakthrough came when women were granted the right to vote. They not only participated in world wars but also led the second wave of feminism that emerged in the tumult of the 1960s. From that moment, historians have increasingly turned their focus to the rich and diverse history of women in Canada. Read more on torontonka.

Within the bustling panorama of Toronto, women waged relentless battles for their equal rights, fuelling the fire with strikes that ignited the city’s heart. The Canadian women’s rights movement grew as a response to the sweeping economic and social transformations driven by the rapid industrialisation of the 19th century. With each generation, as knowledge became more accessible and people moved from rural homes to urban centres, women wielded their weapons of equality with ever-increasing force.

More Than Just the Right to Vote

Many believe that the women’s rights movement in Canada was primarily about securing the right to vote. In reality, it encompassed much more. Numerous women’s organisations that emerged in the mid-19th century also called for improved economic independence and better social conditions for all women.

In 1871, Ontario passed the Married Women’s Property Act, granting women the right to own their income and wages, as well as any profits from businesses they individually owned. Recognising a woman’s legal identity as separate from her husband’s, these early property laws inspired the formation of several women’s rights organisations across Toronto. In the early 19th century, most women in Toronto were homemakers. Some worked as domestic servants or unskilled labourers, while others were sex workers, nuns (in Catholic areas), or teachers. A few served as governesses, laundresses, midwives, seamstresses, or innkeepers.

The Toronto Women’s Literary Club

The Toronto Women’s Literary Club was one such organisation, promoting middle-class ideals of respectability and femininity. Led by Dr. Emily Stowe in 1876, the Literary Club advocated for women’s access to higher education, better working conditions, and participation in the political sphere.

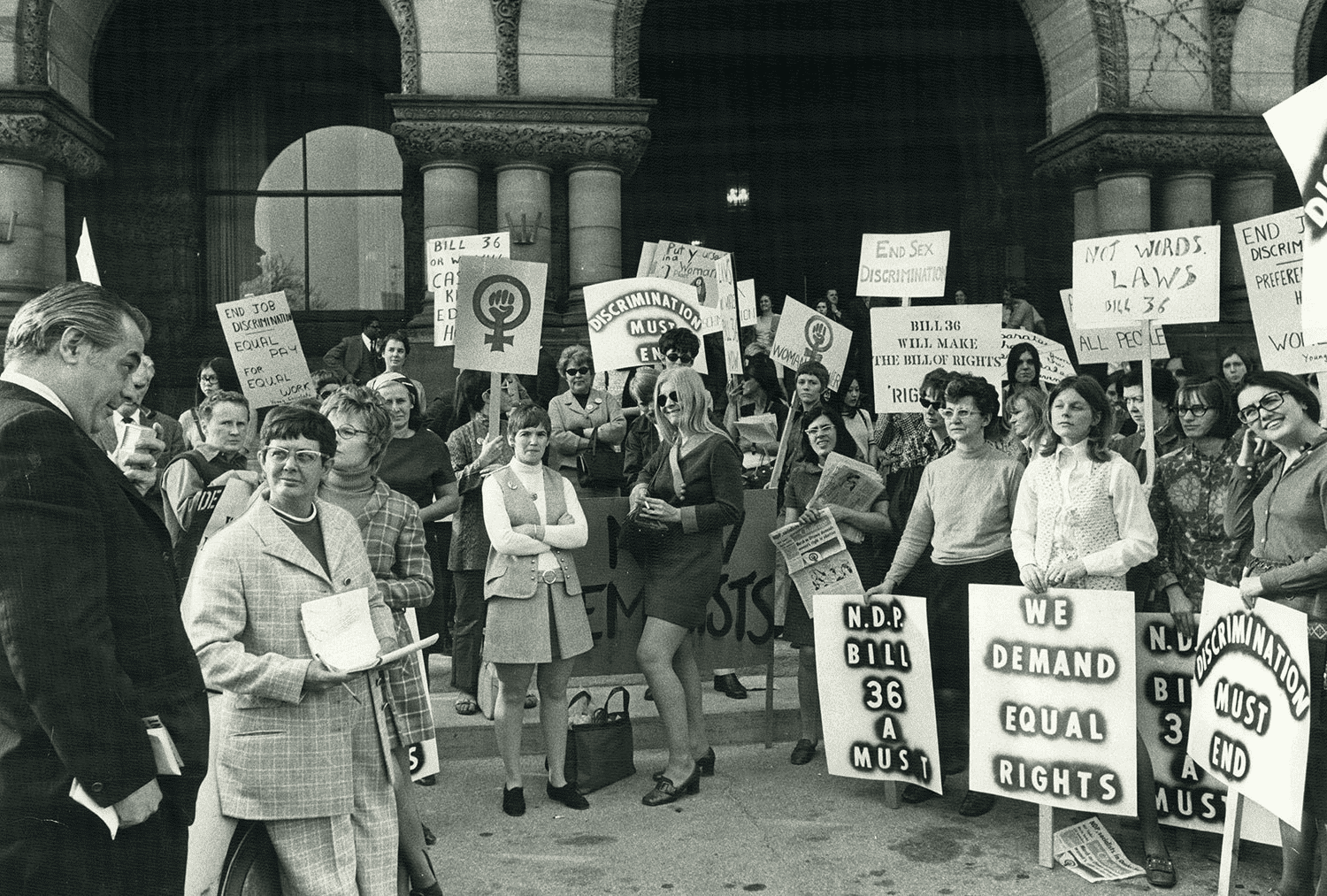

In 1884, the Literary Club renamed itself the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association (CWSA), reflecting its broader mandate to support women’s suffrage. Through its advocacy efforts, Toronto’s women cast their first votes in municipal elections on January 4, 1886. Although this was a small victory, granting women the right to vote in Toronto’s municipal elections, it wasn’t until 1918 that Prime Minister Robert Borden extended full voting rights to women, partly in recognition of their wartime contributions. As women continued to support and participate in World War II, their mobilisation for equal access to jobs and fair pay also grew. Women increasingly joined labour unions and pressured provincial and federal governments to pass legislation supporting working women.

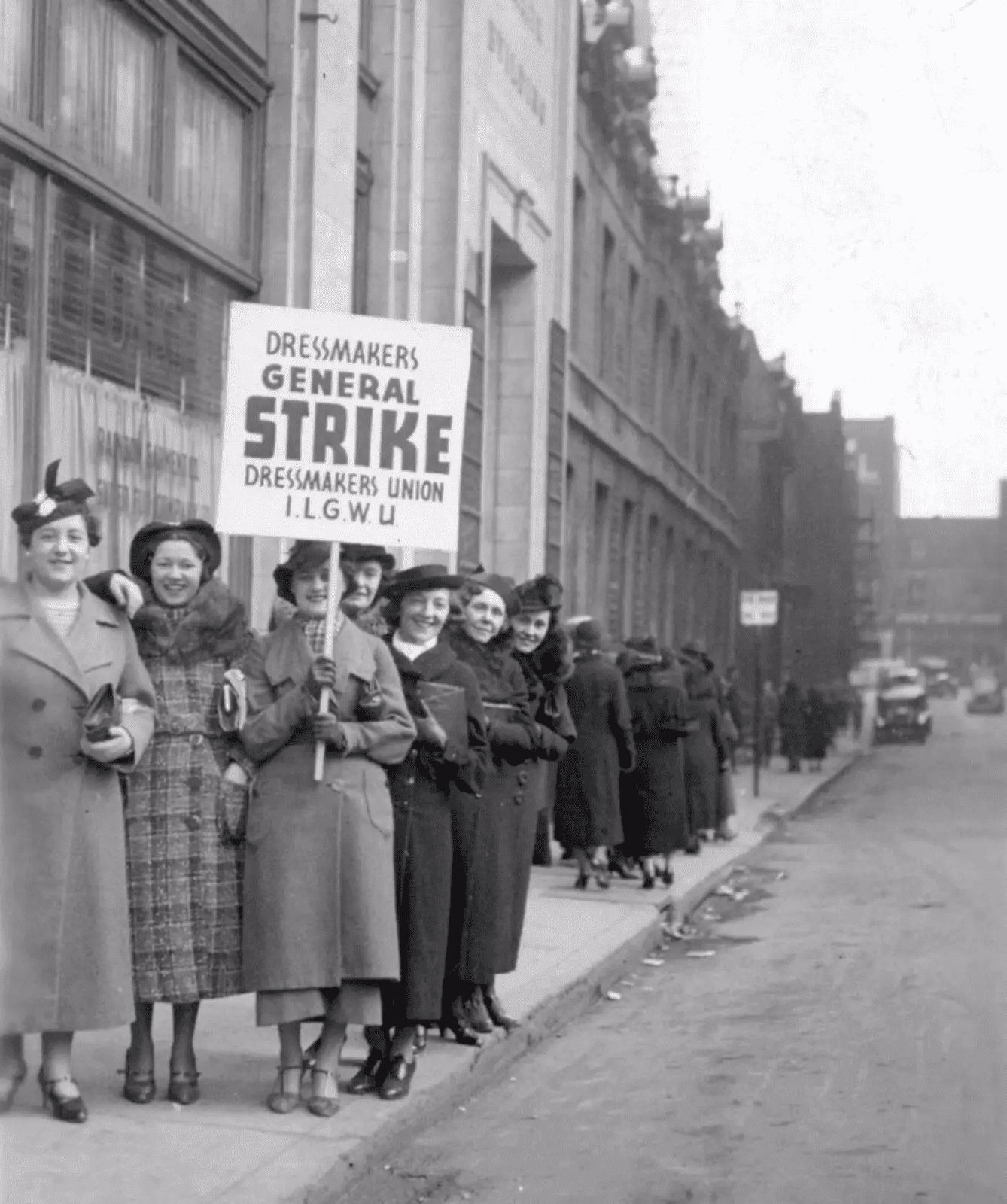

Toronto’s Garment Workers’ Strike

When the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) launched a strike in Toronto in 1931, it highlighted the wage inequalities and workplace harassment faced by many immigrant workers. By 1951, when Ontario passed the Fair Employment Practices Act, women’s union activity and demands for equal pay for equal work had consistently remained high.

However, longstanding racial and gender hierarchies in Canadian society meant that not all women were equally included in the national vision for women’s rights. Indigenous women, for example, did not gain the right to vote until 1960, when the Canadian Bill of Rights allowed them to vote federally without losing their Indian status. Marginalised by the Indian Act and colonial practices, Indigenous women faced barriers to political participation and equal rights, even as their traditional political systems were destabilised.

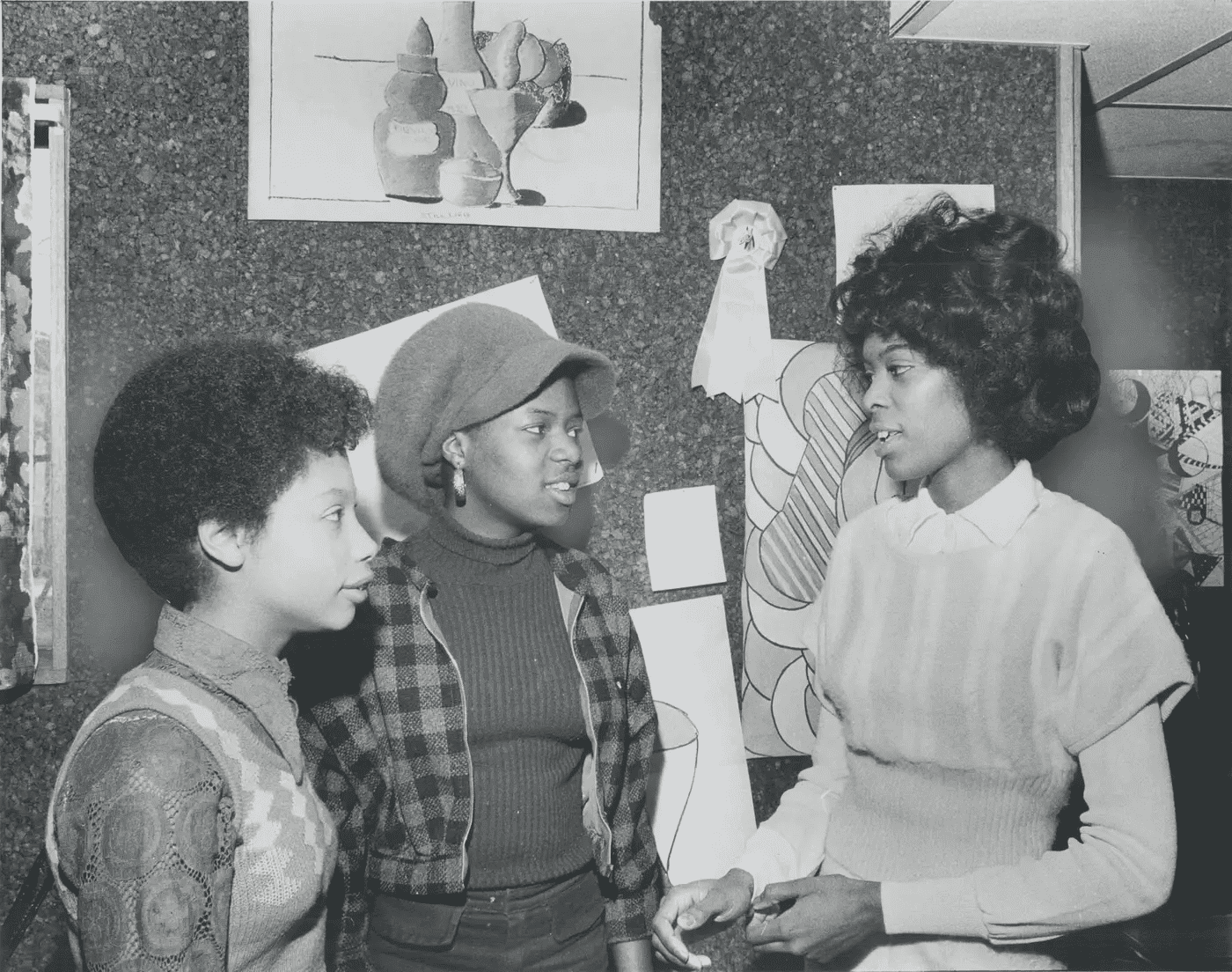

Despite these challenges, members of Indigenous communities, many of them women, founded the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto and the Women’s Auxiliary in 1963. These organisations worked to foster cultural pride and improve access to education and community spaces, reflecting the growing networks of Indigenous activism. Even with the Royal Commission on the Status of Women amplifying feminist activism in the 1960s, Black women in Toronto continued to fight against discrimination in housing, education, and employment. Their activism took many forms, asserting their womanhood while ensuring the survival of their communities and cultures.

The Congress of Black Women of Canada

Building on earlier organisations like the Eureka Club and the Toronto chapter of the Congress of Black Women of Canada, the Black Women’s Collective addressed intersectional issues in the 1980s and advocated for broader representation in national women’s organisations.

As second-wave feminists fought for reproductive rights, a historic Supreme Court decision in 1988 deemed abortion bans unconstitutional. Women activists across Toronto celebrated the legal recognition of a woman’s right to control her own body. In the 1990s and into the 21st century, activists highlighted the growing impact of gender and globalisation, addressing poverty, human rights, violence against women, and transphobia. Women in Toronto harnessed digital platforms and formed coalitions to continue the fight for their rights. The Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action exemplifies the growing network of organisations working to influence national policy changes regarding international human rights.

Women in Toronto persist in challenging the legacies of colonialism, racism, sexism, and global economic interests that perpetuate inequality, doing so through diverse and complex motivations shaped by their experiences and histories in the city.