Toronto has been home to many feminists who have made significant contributions to advancing women’s rights, and Elsie MacGill is among the most remarkable. As an aeronautical engineer, feminist, and the first woman to earn a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, MacGill’s legacy is a testament to determination and innovation. She also served as president of the Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs (CFBPWC). Learn more about her extraordinary life and career at torontonka.com.

Feminism Rooted in Childhood

Elsie MacGill was born on March 27, 1905, in Vancouver, British Columbia. She was the second daughter of Helen and James MacGill. Her mother, Helen Gregory MacGill, was a trailblazer in her own right, becoming the first woman in the British Empire to earn a Bachelor of Music in 1886. In 1890, Helen obtained a Master of Arts in Mental and Moral Philosophy, and in 1917, she became British Columbia’s first female judge.

Helen MacGill’s accomplishments laid a foundation for feminist ideals in her daughters, instilling in Elsie and her older sister a strong belief in gender equality.

Elsie attended public school before enrolling in the Faculty of Applied Science at the University of British Columbia in 1921. In 1923, she transferred to the University of Toronto, where she studied electrical engineering, graduating in 1927. Soon after, she found work in her field, a rarity for women at the time.

A Groundbreaking Career in Aviation

MacGill began her career as a mechanical engineer at an automotive company in Pontiac, Michigan. When the company expanded into aircraft manufacturing, Elsie enrolled at the University of Michigan, earning a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering in 1929. This achievement made her the first woman in the world to hold such a degree.

Shortly after completing her degree, MacGill was diagnosed with polio. Confined to a wheelchair for several years, she turned to writing, penning articles about aviation for British publications and designing aircraft from home. During this time, she also became active in feminist causes led by her mother and joined the CFBPWC.

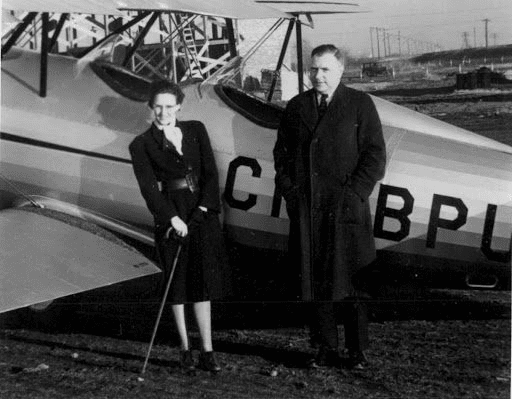

After recovering, MacGill returned to Canada in 1934 and joined Fairchild Aircraft Ltd. as an assistant aeronautical engineer. She designed numerous aircraft and demonstrated her courage by insisting on testing her designs through flight trials, despite the inherent risks.

A Fearless Advocate for Women’s Rights

MacGill believed in driving change through legislative reform and championed several progressive ideas. For example, she argued that women should have full control over their bodies, including the right to access safe abortions—a stance that was controversial at the time, as abortion was illegal under Canada’s criminal code.

In 1947, following her mother’s passing, MacGill published a biography titled My Mother the Judge: A Biography of Helen Gregory MacGill. The book reignited her feminist activism, leading to closer collaboration with the CFBPWC. In 1965, she was elected president of the organization. In this role, she emphasized that Canada’s future would improve through the inclusion of women’s voices and contributions.

From 1967 to 1970, MacGill served on the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada, where her leadership and organizational skills were lauded by the commission’s chair, Florence Bird.

Until her final days, Elsie MacGill continued to work in engineering while passionately advocating for women’s rights. Known for her fearlessness in speaking the truth, MacGill passed away suddenly in the fall of 1980 while visiting her sister. Her death shocked those who knew her, but her legacy endures.

Posthumously, MacGill has received numerous accolades for her remarkable contributions to engineering and feminism. Her life remains an inspiring example of breaking barriers and championing equality.